Adaptation

Tick resistance

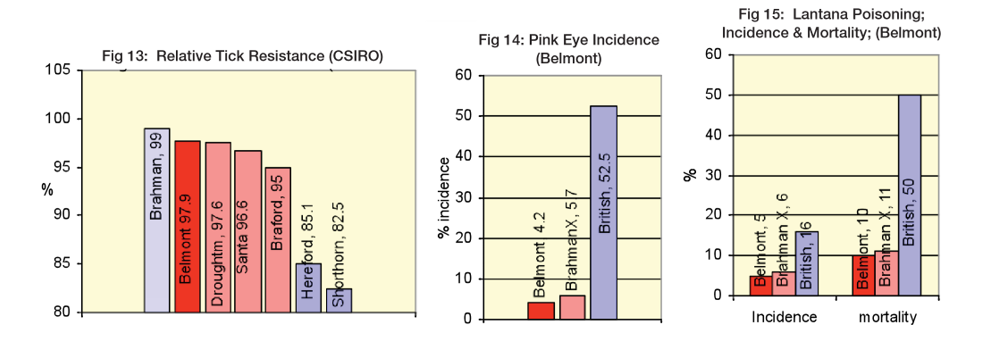

The Belmonts tick resistance of 98% (Fig. 13) means that only 2 of 100 seed ticks complete their lifecycle, while 82% resistance of the Shorthorn means that 18 out of 100 seed ticks survive. The Belmont is therefore 9 times more resistant than the Shorthorn. Using the Belmont is therefore an effective and sustainable method of controlling ticks.

“Brigalow” It required four to six less dipping’s to control cattle tick on Belmonts than for the Herefords and Simmentals. At the time of this study chemical costs were 30 cents per head and represented a saving of $1350 to $2030 for a herd of 1000 adult equivalents. This did not include the value of labour which could be directed towards income earning tasks. In present day terms these figures would be significantly higher.

Belmonts are relatively resistant to the most important blood parasite causing tick fever, Babesia Argentina.

Heat tolerance

“Belmont” Heat stress raises body temperature and respiration rates and depresses food intake. When compared to British breeds, about 25% of the higher growth of Belmonts was accounted for by their heat tolerance. The superior heat tolerance of Belmonts was largely due to their higher sweating capacity and sleeker coats.

Drought tolerance

“Belmont” Heat stress raises body temperature and respiration rates and depresses food intake. When compared to British breeds, about 25% of the higher growth of Belmonts was accounted for by their heat tolerance. The superior heat tolerance of Belmonts was largely due to their higher sweating capacity and sleeker coats.

Disease resistance

“Belmont” Pink Eye (bovine infectious keratoconjunctivitis) infections at 8m of age in the Belmont’s was 4.2%, Brahman Composite 5.7% and British 52.5%. Infection was much more severe in the British breed. Infections signifi cantly affected live weight of all breeds.

Survival and Mortalities

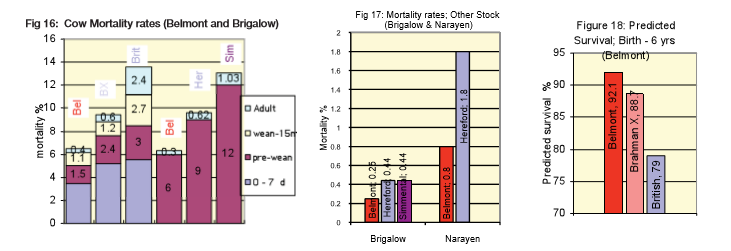

“Belmont” Mortalities of Belmonts (Fig.16) in most age groups were less than half those of the British cross, and slightly less than the Brahman cross. The lower mortalities resulted in a 13% higher survival of cows to 6 years of age for the Belmonts (Fig 18) This gives them a large economic advantage over the British crosses. “Brigalow” Calf losses from pregnancy to weaning were Belmonts 6%, Herefords 9% and Simmental 12% (Fig 16). In addition cost of calving supervision to avoid excessive cow and calf deaths and for animal welfare considerations, was nil for Belmonts but high for Herefords and very high for Simmental. In the breeding cows (Fig 16) death rates were; Belmonts 0.30%, Herefords 0.62% and Simmental 1.03% i.e. mortality rates of Belmonts were less than half that of Herefords and 1/3 that of Simmentals. Similarly in the other classes of stock (Fig 17), mortalities were nearly half those of the Herefords and Simmentals. “Narayen” Calf losses from conception to calving of Belmonts (7% and 2%), were approximately half of that of Herefords (12% and 6%) on Brigalow and Spear grass pastures respectively. Cow mortalities of Belmont’s (0.8%) were also less than half of Herefords (1.8%) (Fig.17)

Lantana Poisoning

“Belmont”. 5% of Belmonts, 6% of Brahman Composites and 16% of British were affected by lantana poisoning. In addition, of the affected animals, 10% of Belmonts, 11% of Brahman-cross and 50% of British died. It was postulated that environmental stress may cause the British to eat more Lantana.

Conclusions on Adaptation

The superior adaptability of the Belmont results in low mortalities. This gives it a large economic advantage over the Temperate breeds in the Tropics and Sub-tropics.